Wolfram's math disproves "intelligent

design"

The math described on this web page is Stephen Wolfram's,

but the subsequent opinions about theology and society are mine.

I am writing this web page because I am

tired of hearing science attacked and undermined by people who do not

understand or respect it.

One formulation of

"intelligent design" can be summarized as follows:

| | (1) |

The world around us is filled with both order and complexity -- "ordered complexity,"

if you will; and |

| |

| | (2) |

such ordered complexity could not have arisen by accident. |

| |

| Therefore |

| |

| | (3) |

there is, or was, some intelligence who designed this world. |

Now, I certainly agree with (1). And although I am not convinced of

(3), I cannot disprove it (see next paragraph). My quarrel is with (2).

If (3) turns out to be true, we may or may not someday

have proof of it. (Some people say we already have

proof, but I mean proof that is strong enough to

convince everyone.)

But if (3) turns out to be false,

we still will never have definitive proof of it.

Indeed,

even if we someday finish filling in all the details

in a scientific explanation of the universe,

so detailed and so supported by evidence that it is

indisputable,

and even if it turns out that god doesn't show

up anywhere in that explanation,

we will still be unable to

rule out the possibility

that some creator built this universe

but -- for reasons known only to him --

intentionally designed it in such a way

as to hide his own part in its creation.

He could have put the fossils

under the mountains, and faked the age

of everything so expertly that he

could fool our carbon-dating

and red-shift measurements.

(Indeed, maybe he created us all

this morning, and gave us fake memories

of what happened yesterday and earlier.)

Some have suggested that he is now sitting in a coffeeshop

somewhere, reading newspaper accounts of

the school board trials, and

chuckling over how he fooled us.

So I am not trying to disprove (3);

I know I can't.

This web page is concerned

only with showing that (2) is not valid reasoning,

and does not constitute a proof of (3).

I assert that statement (2)

is mathematically just plain wrong -- and I assert that

the wrongness of (2) is not merely opinion, but fact. The

people who believe (2) are being rather unimaginative, but in addition

to imagination I can offer evidence.

Stephen Wolfram's book

shows -- with mathematical examples --

how complex systems can arise

from simple ones. I will sketch some of the ideas below.

A cellular automaton is a sort of self-propelled computer program.

You specify the initial conditions and the transformation rules, and

then you tell it to "go," and the program proceeds to do things on its own.

Probably the best known example of a cellular automaton is

the "Game of Life," devised by mathematician

John Horton Conway in 1970 and popularized by

mathematics journalist Martin Gardner in the same year.

You can see an illustration from that game, to the left

of this paragraph. The program operates on a two-dimensional array

of squares. Each square is either black (alive) or white (dead, or empty),

at each instant of time. The status of cell X at time n+1 is determined

by the status of X and its immediate neighbors at time n.

A cellular automaton is a sort of self-propelled computer program.

You specify the initial conditions and the transformation rules, and

then you tell it to "go," and the program proceeds to do things on its own.

Probably the best known example of a cellular automaton is

the "Game of Life," devised by mathematician

John Horton Conway in 1970 and popularized by

mathematics journalist Martin Gardner in the same year.

You can see an illustration from that game, to the left

of this paragraph. The program operates on a two-dimensional array

of squares. Each square is either black (alive) or white (dead, or empty),

at each instant of time. The status of cell X at time n+1 is determined

by the status of X and its immediate neighbors at time n.

The rules are simple enough that

they could easily be programmed into even the rather rudimentary

computers that were available in 1970. Investigating the patterns

of "Life" became a recreational pastime of many programmers.

Nowadays,

if you're interested in seeing more of this game, you don't have

to be a computer programmer; you can just download one

of the programs that someone else has already written for your

personal computer.

Stephen

Wolfram made himself famous (among scientists,

at least) with his creation of Mathematica, a computer

program widely used by scientists since 1988. (See illustration at right.)

The program

continues to improve with new editions. It (and other programs

like it, though Mathematica is the leader in this genre)

have made a new kind of mathematics possible: Mathematics

has always been theorems and proofs, but now it is also

experiments. With just a few minutes' work, a mathematician

can now generate dozens or hundreds of examples and look at

pictures of the results; this makes it easier to discover

conceptual principles that underlie the examples and are

shared by them.

Stephen

Wolfram made himself famous (among scientists,

at least) with his creation of Mathematica, a computer

program widely used by scientists since 1988. (See illustration at right.)

The program

continues to improve with new editions. It (and other programs

like it, though Mathematica is the leader in this genre)

have made a new kind of mathematics possible: Mathematics

has always been theorems and proofs, but now it is also

experiments. With just a few minutes' work, a mathematician

can now generate dozens or hundreds of examples and look at

pictures of the results; this makes it easier to discover

conceptual principles that underlie the examples and are

shared by them.

But for many years Wolfram also worked on

mathematical research,

using such computer experiments. He learned in 1982

that complexity in mathematical systems can arise from

very simple origins. He investigated this idea extensively

for many years.

He finally published some of

his findings in 2002, in an enormous book titled

A New Kind of Science. It was a science book which received

mixed reviews from the scientific community -- not because there was

anything wrong with Wolfram's science, but because of the slightly

unconventional way that he published it: as a large, popular, expository,

self-published book, rather than as a specialized, arcane article

in a peer-reviewed journal.

Wolfram did not publish the book

for profit -- you can read

the book for free online

if you simply register. If you want a printed copy,

don't bother printing it out yourself --

your costs won't be much less than what Wolfram is charging for a very

nicely bound copy.

Wolfram studied many examples of simple mathematical systems that

give rise to complexity. Featured prominently

in the book is one class of 256 experiments which might

be termed the simplest possible cellular automata; they are simpler

than the "game of life."

Each of these automata acts on a row (i.e., a one-dimensional array) of

black and white squares, but we get an interesting two-dimensional

picture by stacking the rows -- i.e., the row at time 1, and below

it the row at time 2, and below it the row at time 3, etc.

Wolfram studied many examples of simple mathematical systems that

give rise to complexity. Featured prominently

in the book is one class of 256 experiments which might

be termed the simplest possible cellular automata; they are simpler

than the "game of life."

Each of these automata acts on a row (i.e., a one-dimensional array) of

black and white squares, but we get an interesting two-dimensional

picture by stacking the rows -- i.e., the row at time 1, and below

it the row at time 2, and below it the row at time 3, etc.

Each picture is generated by an extremely simple rule

-- one that could easily

occur "by accident" in nature, as it were -- but many

of the pictures show incredible ordered complexity.

For instance, a small portion of

picture number 30 is shown at the right. You can

see that its right half is very disordered, but some

order is apparent on the left half. And the whole

picture is very complicated; yet it is generated by a very simple rule.

In each picture, the top row has only one black square.

In rows below that, each cell's behavior (black or white)

is determined by the

behavior of the three cells above it

(directly above, diagonally left, and diagonally right).

There are 2x2x2 = 8 possible

behaviors of those three cells:

black-black-black, black-black-white, and so on. For each of those

8 combinations, the rule must specify either a black result or a white result

in the new row.

Thus, to specify a rule, we must specify 8 yes-or-no choices.

The number of rules of this sort is therefore

2x2x2x2x2x2x2x2 = 256.

The book's website includes a very nice one-page summary of this idea, including some pictures that illustrate

rule 30, rule 90, and rule 254.

In each picture, the top row has only one black square.

In rows below that, each cell's behavior (black or white)

is determined by the

behavior of the three cells above it

(directly above, diagonally left, and diagonally right).

There are 2x2x2 = 8 possible

behaviors of those three cells:

black-black-black, black-black-white, and so on. For each of those

8 combinations, the rule must specify either a black result or a white result

in the new row.

Thus, to specify a rule, we must specify 8 yes-or-no choices.

The number of rules of this sort is therefore

2x2x2x2x2x2x2x2 = 256.

The book's website includes a very nice one-page summary of this idea, including some pictures that illustrate

rule 30, rule 90, and rule 254.

Another way to get complicated pictures from simple rules

is to use points on a plane instead of black and white squares.

Another way to get complicated pictures from simple rules

is to use points on a plane instead of black and white squares.

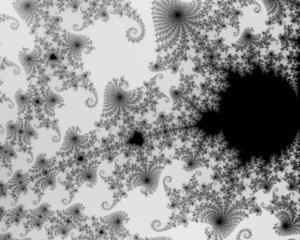

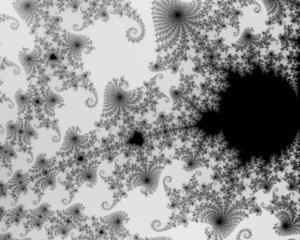

Fractals

have been popular among mathematicians since their

study was made possible by modern computers around the

mid-1970's; some of

these immensely complicated pictures are generated by very simple

rules. For instance, the

Mandelbrot set,

shown at right,

consists of the set

of points c in the complex plane for which the iteratively defined sequence

Fractals

have been popular among mathematicians since their

study was made possible by modern computers around the

mid-1970's; some of

these immensely complicated pictures are generated by very simple

rules. For instance, the

Mandelbrot set,

shown at right,

consists of the set

of points c in the complex plane for which the iteratively defined sequence

z0 = 0, zn+1 = zn2 + c

does not tend to infinity. Iterative applications of simple rules produce many amazing fractal

images, and some of them strongly resemble images seen in nature. An example of this is

Barnsley's fern, shown at left.

The works described above are experiments conducted on computers,

but the ideas are mathematical. The certainty of mathematics is greater

than that of any of the other sciences. In a chemistry or physics experiment,

there is always the possibility that the outcome is influenced by some phenomena

that have not yet been observed -- e.g., that our instruments aren't sensitive enough,

or our perception is not unbiased enough. But a problem in mathematics is finite;

a mathematics problem

has only the ingredients that are put into the problem by the mathematician.

There are no hidden influences, and so we can be completely certain of the outcome.

Wolfram's book does mention some of the similarities

between mathematically generated patterns and patterns in nature.

Wolfram also

mentions intelligent design very briefly,

both with regard to complexity

and with regard to purpose.

But for the most part he avoids the controversy. After all, his book is one

of science, not sociology or politics.

But I will face that controversy right here, because I am tired of hearing

people who understand nothing of science claiming that they have an

equally justifiable explanation of things.

The advocates of intelligent design are simply

wrong when they say that ordered complexity cannot occur by accident.

Wolfram's mathematics shows in examples that

ordered complexity does occur by accident.

But I will face that controversy right here, because I am tired of hearing

people who understand nothing of science claiming that they have an

equally justifiable explanation of things.

The advocates of intelligent design are simply

wrong when they say that ordered complexity cannot occur by accident.

Wolfram's mathematics shows in examples that

ordered complexity does occur by accident.

Let me emphasize that I am not asserting

the nonexistence of God.

If you want to believe in a God, I won't dispute it; I just hope

that ordered complexity isn't the foundation of your belief.

Most of us prefer to believe in whatever is

the simplest explanation

that fits all the facts. Scientists often

call this a principle of science, but most

non-scientists follow this rule too.

However, what is "simplest" is

a somewhat subjective matter.

For instance, what makes an automobile go? It is

"the internal combustion engine" if you have studied

and understand

such things, or if you at least have some respect for

the people who built the car or who know how to repair it.

But it is "magic"

if you have neither that understanding nor that respect.

Most people in our society do respect their

automobile mechanics. I'm

sorry that so many people don't have

the same respect for

biology researchers,

who trained for much longer.

If you want to teach creationism or "intelligent design"

in science classes in

schools, I think you should explain it to students this way:

Some people prefer to believe in creationism or

"intelligent design" because they find that explanation

simpler than the secular view that is prevalent in

the scientific community -- though that preference reflects

their own lack of understanding of the ideas that the

scientific community has produced. One of the goals

of this science class is to explain evolution

so that you do understand it.

Moreover, despite overwhelming evidence (perhaps because they

have not looked at the evidence), some

people continue to believe that the universe cannot be

explained without the presence of a creator. One of the

goals of this science course is to show you that it

can be explained without that additional assumption.

By the way, the Wolfram examples only show complexity

building upward, but biological evolution has other

mechanisms available too, involving the removal of

structures. Don Lindsay, a computer scientist,

has posted a particularly clear

web page explaining some of these mechanisms.

Still another point of confusion may stem from the general

public's poor understanding of probability. (The lottery is a tax

levied on people who do not know math.) I think that most

scientists would agree that relatively few planets are suitable

for the origination of life -- i.e., if you pick a planet at

random, there's very little chance that it will be a planet where

life can develop. However, that does not mean that our

being on such a planet is unlikely. To understand the question,

you have to turn it around and ask it the other way. Given

that we did wake up one day (or one millenium) and start asking

questions, what are the odds that we did it on one of the

few planets capable of sustaining life? Very high, obviously.

Or here is still another way to put the question: There are

billions of planets in the universe. No two are identical, but

we could classify them into certain "types" according to whether

they have similar chemical compositions, axial tilts, distance

from their parent stars, and so on. Is there a certain "type"

of planet on which life is highly likely to evolve?

Most astrobiologists would say yes. If you're interested

in this sort of question, you might want to look at Wiki's

discussion of the

Drake equation.

Why does it matter? What is the harm in introducing

a bit of theology in a science class?

Well, science and theology operate on entirely different

principles, and belong in different places.

-

The "scientific method"

operates on these principles: Question everything

and everyone, even your teachers. A document's

great age does not make it authoritative;

there is no authority

except repeatable experimental evidence and pure reason.

Moreover,

one must constantly be on guard against biases

(accidental or otherwise) in the

experiments or implicit assumptions in the reasoning.

No answer is ever final -- an established tradition

can be overthrown instantly

if its experimental evidence is shown

to have overlooked something or to be faulty in

some other respect -- but until such an overthrow,

proper respect must be given to

"theories" that are supported by overwhelming evidence.

-

Theology, on the other hand, operates on rather

different principles. I'm not sure what they are --

I'm no expert on theology -- but authority and tradition

appear to play bigger roles, and experiment plays a

much smaller role, as far as I can see.

If you label theology as "science" and teach it as such

in a science classroom, you are simply lying. Some students

will be fooled, and will end up with a rather poor understanding

of the scientific method. (Perhaps that is the goal

of some creationists?)

Other students will not be fooled, and

will end up disrespecting the school system.

I find both those outcomes

to be highly undesirable.

In addition to purely philosophical reasons, there are also

practical reasons.

As historian Edward J. Larson has

explained,

the evolutionary viewpoint has been confirmed by its measurable productivity:

Its insights have led to discoveries in medicine, biotechnology, etc. -- i.e., it

has improved our lives. Its lessons should not be denied to our

students, nor obscured by unrelated notions.

an essay by Eric Schechter,

version of 9 April 2006.

A cellular automaton is a sort of self-propelled computer program.

You specify the initial conditions and the transformation rules, and

then you tell it to "go," and the program proceeds to do things on its own.

Probably the best known example of a cellular automaton is

the "Game of Life," devised by mathematician

John Horton Conway in 1970 and popularized by

mathematics journalist Martin Gardner in the same year.

You can see an illustration from that game, to the left

of this paragraph. The program operates on a two-dimensional array

of squares. Each square is either black (alive) or white (dead, or empty),

at each instant of time. The status of cell X at time

A cellular automaton is a sort of self-propelled computer program.

You specify the initial conditions and the transformation rules, and

then you tell it to "go," and the program proceeds to do things on its own.

Probably the best known example of a cellular automaton is

the "Game of Life," devised by mathematician

John Horton Conway in 1970 and popularized by

mathematics journalist Martin Gardner in the same year.

You can see an illustration from that game, to the left

of this paragraph. The program operates on a two-dimensional array

of squares. Each square is either black (alive) or white (dead, or empty),

at each instant of time. The status of cell X at time

Wolfram studied many examples of simple mathematical systems that

give rise to complexity. Featured prominently

in the book is one class of 256 experiments which might

be termed the simplest possible cellular automata; they are simpler

than the "game of life."

Each of these automata acts on a row (i.e., a one-dimensional array) of

black and white squares, but we get an interesting two-dimensional

picture by stacking the rows -- i.e., the row at time 1, and below

it the row at time 2, and below it the row at time 3, etc.

Wolfram studied many examples of simple mathematical systems that

give rise to complexity. Featured prominently

in the book is one class of 256 experiments which might

be termed the simplest possible cellular automata; they are simpler

than the "game of life."

Each of these automata acts on a row (i.e., a one-dimensional array) of

black and white squares, but we get an interesting two-dimensional

picture by stacking the rows -- i.e., the row at time 1, and below

it the row at time 2, and below it the row at time 3, etc.

In each picture, the top row has only one black square.

In rows below that, each cell's behavior (black or white)

is determined by the

behavior of the three cells above it

(directly above, diagonally left, and diagonally right).

There are

In each picture, the top row has only one black square.

In rows below that, each cell's behavior (black or white)

is determined by the

behavior of the three cells above it

(directly above, diagonally left, and diagonally right).

There are  Another way to get complicated pictures from simple rules

is to use points on a plane instead of black and white squares.

Another way to get complicated pictures from simple rules

is to use points on a plane instead of black and white squares.

But I will face that controversy right here, because I am tired of hearing

people who understand nothing of science claiming that they have an

equally justifiable explanation of things.

The advocates of intelligent design are simply

wrong when they say that ordered complexity cannot occur by accident.

Wolfram's mathematics shows in examples that

ordered complexity does occur by accident.

But I will face that controversy right here, because I am tired of hearing

people who understand nothing of science claiming that they have an

equally justifiable explanation of things.

The advocates of intelligent design are simply

wrong when they say that ordered complexity cannot occur by accident.

Wolfram's mathematics shows in examples that

ordered complexity does occur by accident.